- Available now

- New eBook additions

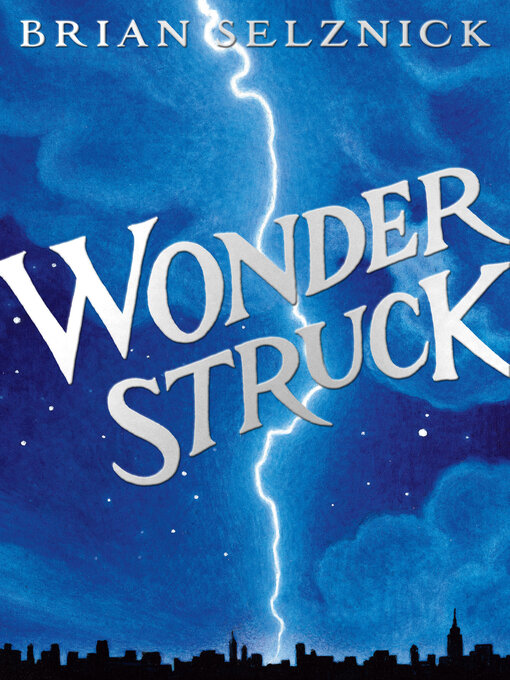

- New kids additions

- New teen additions

- Most popular

- Beloved: Celebrating the Work of Toni Morrison

- Where the Crawdads Sing Read Alikes

- Try something different

- See all ebooks collections

- Available now

- New audiobook additions

- New kids additions

- New teen additions

- Most popular

- Try something different

- See all audiobooks collections